Ce qu’il faut retenir

A routine French naval deployment in the Gulf of Guinea has become the latest flash-point in Sahelian geopolitics. The helicopter carrier Tonnerre docked in Cotonou from 5 to 9 November under Operation Corymbe, yet its presence was swiftly recast by Niger’s ruling junta as evidence of a French plot to invade.

- Ce qu’il faut retenir

- Contexte, entre Paris et l’AES

- Calendrier de l’escale de Cotonou

- Capacités réelles du PHA Tonnerre

- Corymbe et Grand African Nemo: architecture sécuritaire

- Acteurs régionaux en première ligne

- Scénarios de désinformation et riposte diplomatique

- Economic stakes of Gulf shipping

- Role of ECOWAS communication strategy

- Implications pour la gouvernance maritime ouest-africaine

- What next for Niamey and Cotonou?

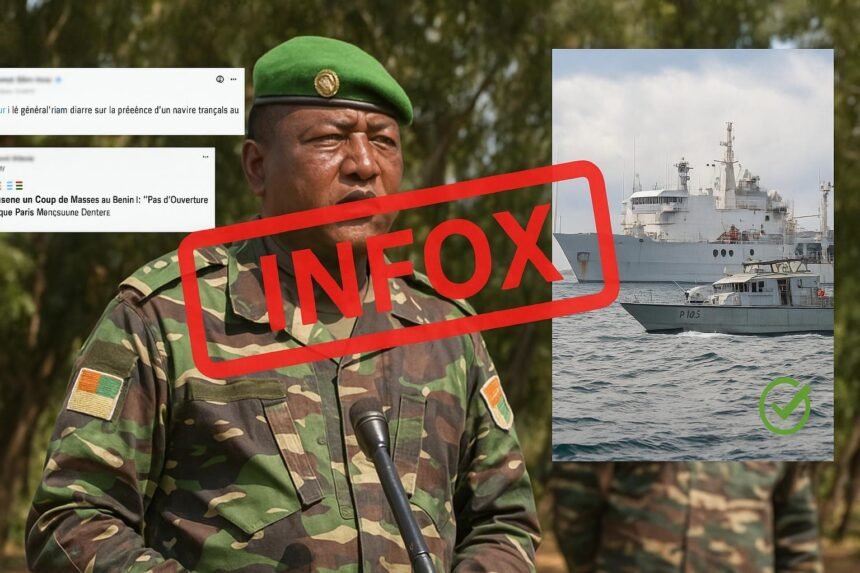

General Abdourahamane Tiani told troops in Dosso on 8 November that “thousands of French soldiers” had been secretly landed in Benin during ten alleged amphibious operations. The claim, unsupported by imagery or eyewitness accounts, feeds a broader narrative portraying Paris as the invisible hand behind regional instability.

Contexte, entre Paris et l’AES

Relations between France and the Alliance des États du Sahel—Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger—have deteriorated since successive coups forced French forces to leave Bamako, Ouagadougou and Niamey. Each capital accuses Paris of asymmetric interference, while France insists it merely redeploys assets to coastal partners such as Benin to uphold maritime security.

Calendrier de l’escale de Cotonou

According to the French Armed Forces Headquarters, Tonnerre’s stopover was announced weeks in advance and publicised by the French embassy’s Facebook page. From Cotonou the 20 000-ton vessel is scheduled to conduct joint drills with eighteen navies, sailing onward to Dakar, Luanda and Duala before returning to Toulon in December.

Capacités réelles du PHA Tonnerre

Despite its imposing 200-metre silhouette, Tonnerre carries at most 900 troops for brief amphibious missions; the present deployment counts roughly 450 personnel plus armoured vehicles and helicopters. No French convoy has been filmed leaving Cotonou’s well-watched port, making the alleged landing of “thousands” of troops virtually impossible to conceal.

Corymbe et Grand African Nemo: architecture sécuritaire

Launched in 1990, Operation Corymbe maintains an almost permanent French naval presence between Senegal and Angola, complementing the eight-year-old Grand African Nemo exercise that trains regional crews in anti-piracy boarding, oil-terminal protection and search-and-rescue. Coastal states value these manoeuvres as force multipliers, especially as pirate attacks shift southward from Nigeria’s delta.

Acteurs régionaux en première ligne

Benin’s navy, operating just three patrol craft a decade ago, now fields modern OPV-45 cutters and a maritime operations centre backed by EU and US funding. Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and Cameroon show comparable upgrades. French training therefore inserts into increasingly capable fleets rather than creating dependency, a nuance often missing in Sahelian rhetoric.

Scénarios de désinformation et riposte diplomatique

The junta’s charge slots neatly into a well-worn playbook: spotlight a visible Western asset, inflate its purpose, and frame domestic hardship as externally orchestrated. Analysts in Abuja and Lomé note that by projecting an external threat, Niamey hopes to consolidate popular support while diverting attention from sanctions and economic headwinds.

Paris, for its part, avoids escalation. Statements limit themselves to technical clarifications and to reiterating commitment to the Yaoundé Code of Conduct on maritime security. Cotonou likewise downplays controversy, mindful of cross-border trade with Niger but determined to preserve defence partnerships that have reduced piracy incidents off Beninese coasts by half since 2021.

Economic stakes of Gulf shipping

The Gulf of Guinea handles nearly 6 percent of global petroleum exports and supplies refined products to landlocked Niger. Any perception of militarisation can jolt freight premiums; London insurers raised rates by 15 percent following the 2020 piracy spike, a cost still felt by import-dependent economies from Togo to Liberia.

Beninese officials estimate that unchecked rumours have already delayed four tanker arrivals this month, forcing the Port Authority to reroute cargo to Lagos. Such distortions translate into higher pump prices and, ultimately, sociopolitical pressure that juntas can harness to justify additional exceptional measures at home.

Role of ECOWAS communication strategy

ECOWAS planners are reviewing a crisis-communication toolkit that would mesh naval Automatic Identification System feeds with public dashboards, allowing citizens to verify ship positions independently. The initiative, championed by Ghana’s Information Ministry, seeks to inoculate social media users against fabricated troop-landing stories and complements the bloc’s existing Early Warning Mechanism.

Implications pour la gouvernance maritime ouest-africaine

Mis- and disinformation cloud already fragile cooperative frameworks. If coastal states perceive international patrols as neo-colonial rather than complementary, enthusiasm for information-sharing could wane, weakening the regional Inter-Regional Coordination Centre in Yaoundé. Transparent public diplomacy, including real-time publishing of ship movements, may therefore be as critical as radar coverage in reassuring stakeholders.

What next for Niamey and Cotonou?

Diplomats in Accra envisage back-channel talks under ECOWAS auspices once Niger appoints a civilian-led transition timetable. Until then Benin’s corridors to the Sahel remain closed, costing Niamey an estimated two-thirds of its seaborne trade. The Tonnerre episode illustrates how maritime logistics can morph into strategic narratives that shape continental alignments.