Ce qu’il faut retenir

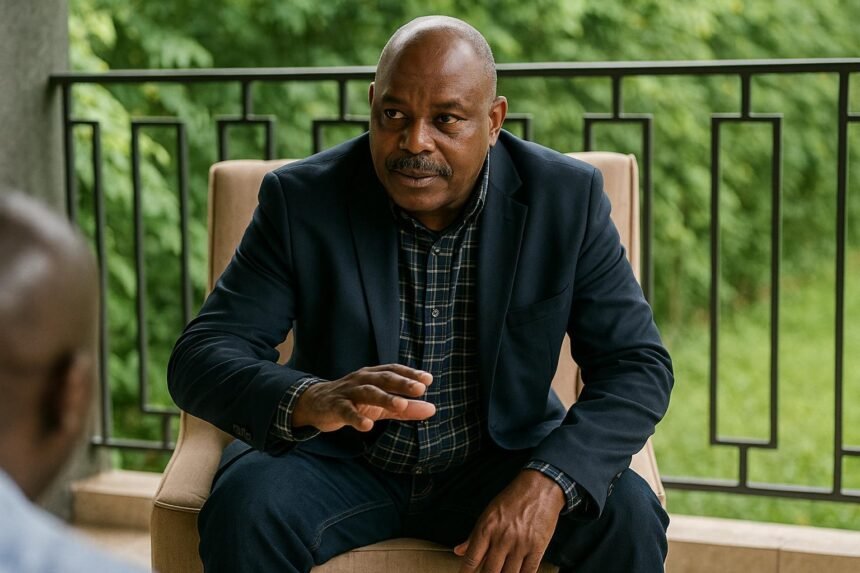

Images of former president Joseph Kabila in Nairobi ended months of speculation over his whereabouts and set the stage for a fresh confrontation with Kinshasa. Joined by ex-prime minister Augustin Matata Ponyo and ten other opposition figures, Kabila announced a movement to “save” DR Congo, accusing President Félix Tshisekedi of sliding toward dictatorship.

Background of legal turmoil

Kabila, who ruled the country from 2001 to 2019, was sentenced to death in absentia by a military court on charges of war crimes and treason. He dismissed the verdict as arbitrary and never appeared in court. Ponyo, equally embattled, received a ten-year sentence for corruption in May, reinforcing the narrative of leaders forced abroad by legal pressure.

The Nairobi declaration

Across two days of closed-door talks in the Kenyan capital, twelve opposition groups drafted a 14-point communiqué calling on Congolese citizens to take “daily actions” to restore dignity and democratic rule. The document condemns alleged arbitrary detentions, judicial harassment of critics, and what participants describe as the government’s refusal of inclusive dialogue.

Critique of governance

Signatories argue that, despite controlling every lever of state power, President Tshisekedi has not enacted policies capable of meeting urgent public needs. They highlight economic mismanagement and deepening insecurity as evidence that the administration is faltering. Government spokesman Patrick Muyaya dismissed the Nairobi gathering as a “non-event” involving “fugitives and convicts,” underscoring mutual hostility.

Kenya’s delicate position

Nairobi has often positioned itself as a mediator in Great Lakes disputes, yet hosting figures linked—by Kinshasa at least—to the M23 rebellion risks straining bilateral ties. Kenya’s foreign ministry has remained silent on the recent meeting, echoing a similar reticence last year when opposition leader Corneille Nangaa announced the creation of the Alliance Fleuve Congo from the same city.

Shadow of the M23 insurgency

M23 rebels currently control swathes of eastern DR Congo, fuelling humanitarian distress and regional friction. Tshisekedi accuses Kabila of masterminding the group, an allegation that paved the way for the former president’s prosecution after senators lifted his immunity. Opposition figures deny any operational link, but the charge adds a security dimension to what is also a high-stakes political contest.

Doha ceasefire oversight

While Nairobi hosted dissidents, Kinshasa inked an agreement in Doha with M23 representatives to establish a monitoring mechanism for their fragile ceasefire. Whether the new opposition drive derails or accelerates that process remains uncertain, yet the coincidence of timelines illustrates how diplomatic, military and legal theatres intersect in DR Congo’s conflict matrix.

Diplomatic offensive promised

The Nairobi cohort pledged to bring their grievances before international forums, arguing that coordinated pressure is vital to avert further instability. They frame their campaign as a defence of constitutional order, seeking solidarity from regional blocs and global partners. For Kinshasa, however, such lobbying may be read as an attempt to legitimise actors already condemned by its judiciary.

Government’s communication strategy

Labeling the gathering a cabal of criminals allows the Tshisekedi administration to cast legal outcomes as victories for accountability. Yet the sharper the rhetoric, the higher the stakes for convincing citizens and donors that courts operate independently. Both camps therefore court international opinion, mindful that external perceptions shape aid, investment and security cooperation.

Possible scenarios

Should the opposition mobilise significant domestic support, Kinshasa might intensify legal proceedings or seek new arrests, risking further polarisation. Conversely, sustained government control could push dissent deeper into exile politics. A negotiated middle path—perhaps revisiting broader dialogue frameworks—remains conceivable but hinges on mutual trust that is presently scarce.

Regional reverberations

Instability in DR Congo resonates far beyond its borders, affecting trade corridors and humanitarian flows across Central and East Africa. Neighbouring states eye the crisis warily, balancing security concerns with opportunities for mediation. The Nairobi episode, therefore, is as much a test of regional diplomacy as it is of Congolese statecraft.

Looking ahead

Kabila’s re-emergence adds a volatile ingredient to an already complex equation that includes ongoing insurgency, contentious court rulings and fragile ceasefires. Whether this latest alliance catalyses meaningful change or deepens divisions will depend on its capacity to galvanise grassroots action and on the government’s response. For now, the political temperature in DR Congo has unmistakably risen.