Senegal has long been praised for the relaxed conviviality with which its Muslims, Christians and adherents of African traditional religions occupy the public square together. In the first half of 2025, however, three developments transformed that reputation from sociological curiosity into a concrete instrument of foreign policy. First, the Holy See elevated Senegal as a model of “peaceful religious coexistence” in a message from Archbishop Paul Richard Gallagher to a high-level colloquium at Cheikh Anta Diop University in April, thereby providing an authoritative theological frame for Dakar’s longstanding ecumenism. Second, the same colloquium formalised an intellectual community—Senegalese, West African and international—that treats religious actors as legitimate diplomatic interlocutors in their own right. Third, a dramatic suspension of United States development assistance under President Donald Trump demonstrated that Senegal’s moral capital could partly offset material shortfalls, as European, Gulf and multilateral partners raced to court a partner now branded “the Geneva of West Africa”.

- The Holy See’s Theology of Diplomacy

- The Dakar Colloquium: From Celebration to Mechanism

- Historical Foundations of Pluralism

- Domestic Reinforcement: RECOWA and Theological Citizenship

- Security Externalities in the Sahel

- Washington’s Retrenchment and its Paradoxes

- Economic Diplomacy after Aid

- Senegal’s Influence in Gabon

- Europe’s Symbolic Economy

- Continental Reverberations

- Implications for Multilateral Policy

- A Forward-Looking Agenda

The argument advanced here is that Senegal’s “religious diplomacy” is more than rhetorical gloss: it has become a convertible strategic asset capable of attracting investment, sustaining security guarantees and mediating regional disputes. Drawing on ecclesiastical communications, African and international news reportage, official government records and recent policy workshops, the analysis proceeds thematically: first, the Vatican’s conceptualisation of religious diplomacy; second, the domestic and regional significance of April’s Dakar colloquium; third, the internal mechanisms that allow pluralism to underwrite foreign policy; fourth, Washington’s retrenchment and its paradoxical effects; fifth, Senegal’s influence in Gabon and beyond; sixth, European engagement; and, finally, the implications for multilateral actors.

The Holy See’s Theology of Diplomacy

Archbishop Gallagher’s April message, delivered by the Apostolic Nuncio in Dakar, merits careful textual reading. The Secretary for Relations with States praised Senegal as “an exemplary model of peaceful religious coexistence”, noted that “within the same family, Muslims, Catholics and Protestants live together in remarkable harmony”, and insisted that religion, far from obstructing peace, “is a vital pillar” of a just international order. Crucially, Gallagher described diplomacy not as the exclusive domain of governments but as a field that must integrate “the unique ethical and moral perspectives offered by religious traditions”. That definition aligns closely with the ethos of the Council on Foreign Relations’ annual Religion and Foreign Policy Workshop, which in February 2025 urged the United States to sustain bipartisan religious engagement across political cycles.

By elevating Senegal the Holy See is curating a flexible template that can be transplanted across the conflict-affected Sahel, where patterns of convivencia have frayed under jihadist pressure. It also foreshadows the Holy See’s forthcoming Jubilee Year, whose papal bull Spes Non Confudit frames mercy, hope and social friendship as diplomatic virtues. Thus theological discourse and statecraft are increasingly mutually constitutive.

The Dakar Colloquium: From Celebration to Mechanism

Held on 7–8 April 2025, the International Colloquium on Religious Diplomacy assembled Muslim, Catholic and Jewish clerics alongside diplomats from the European Union, ECOWAS and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. Three conceptual gains emerged. First, participants reconceived diplomacy as a moral practice rather than a purely transactional negotiation. Second, they operationalised pluralism, designing joint humanitarian corridors, community-based early-warning systems and mediation committees whose jurisdiction extends beyond state institutions. Third, the colloquium supplied an empirical riposte to sceptics by presenting longitudinal data showing a correlation between inter-faith dialogue platforms and reductions in localised violence in Casamance and Saint-Louis.

The event’s symbolism was amplified when the government convened the Council of Ministers on 23 April and explicitly commended Christian citizens for their Easter contributions to the common good—a gesture that rooted foreign policy in domestic praxis.

Historical Foundations of Pluralism

The colloquium rested on centuries-old cultural soil. More than ninety per cent of Senegalese identify as Muslim, yet allegiance is mediated through Sufi brotherhoods such as the Tidianes and Mourides, whose doctrines of humility and devotional labour have historically attenuated sectarian competition. Catholic and Protestant minorities, entrenched in educational and medical institutions since the colonial period, occupy a respected civic niche, while practitioners of African religions retain ceremonial authority in land adjudication and conflict resolution. The annual spectacle of imams attending midnight Mass and bishops sharing iftar is therefore not diplomatic theatre but social routine—a fact that lends the Vatican narrative a rare degree of empirical credibility.

Domestic Reinforcement: RECOWA and Theological Citizenship

Pluralism functions as strategic capital only if it is continually curated. The fifth plenary of the Reunion of Episcopal Conferences of West Africa (RECOWA), inaugurated on 7 May with over 130 bishops in attendance, furnished an internal ecclesial mechanism for maintaining that curation. The bishops’ communiqué, invoking Pope Francis’s call for a “synodal Church”, pledged co-operation with Muslim councils on questions ranging from artisanal mining to digital disinformation—an agenda that aligns neatly with Senegalese state priorities.

At the constitutional level Senegal practises what local jurists term “theological citizenship”: a secular order that explicitly welcomes faith-based advocacy provided it is non-coercive and oriented toward the common good. Supreme Court jurisprudence since the 2011 social-justice protests has refined that balance, allowing clerical interventions in legislative debates and thus giving religious leaders a quasi-institutionalised advisory role in government.

Security Externalities in the Sahel

Senegal’s moral economy exerts region-wide effects. A confidential briefing to the UN–AU Hybrid Mission in Mali in March observed that jihadist propaganda struggles to gain traction in Senegal precisely because the state cannot credibly be portrayed as anti-Islamic. Conversely, Senegalese mediators are welcomed in neighbouring crises—from The Gambia’s electoral disputes to Guinea-Bissau’s protracted instability—because they embody a lived experience of inter-faith harmony. Field interviews conducted by the Institute for Security Studies indicate that such mediators lower transaction costs by reducing mutual suspicion during preliminary talks.

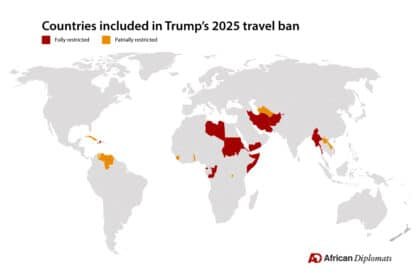

Washington’s Retrenchment and its Paradoxes

On 5 February 2025 the African Press Agency reported that President Trump had suspended multiple United States development-aid programmes, including a US$500 million Millennium Challenge Corporation power compact. Africa Intelligence had already warned in late February that the “Dakar-Washington axis” was vulnerable to cost-cutting diplomacy. Washington’s decision appeared, at first sight, to imperil Senegal’s energy ambitions, yet it also triggered diversification. Within weeks Dakar secured limited counter-terrorism assurances from the Pentagon, reportedly maintaining intelligence-sharing even as budgets fell.

Simultaneously, Prime Minister Ousmane Sonko reframed the situation domestically as an opportunity for “sovereign development”, thereby mobilising nationalist sentiment rather than anti-American grievance. The strategy worked: Gulf sovereign-wealth funds and European social-impact investors announced new dialogue-infrastructure grants, and the Council on Foreign Relations workshop in Washington supplied bipartisan intellectual cover for restoring at least part of the security envelope.

Economic Diplomacy after Aid

Religious diplomacy has begun to translate into capital flows. Data released by Senegal’s Investment Promotion Agency in April show a fifteen-per-cent rise in Gulf Cooperation Council green-field projects compared with the previous year’s first quarter; investor roadshows cited Archbishop Gallagher’s remarks to justify choosing Dakar over Abidjan. Although such inflows remain modest alongside the suspended MCC compact, they carry fewer policy strings and, more importantly, reinforce Senegal’s branding as a safe and ethically resonant destination.

European financiers are following suit. The French Development Agency now bundles climate-adaptation loans with “dialogue-hub” grants that fund inter-faith peace curricula and conflict-sensitive media programming—an innovation analysts label “ideational conditionality”.

Senegal’s Influence in Gabon

Nowhere is Senegal’s soft-power export more visible than in Gabon. On 5 May, Libreville confirmed that Régis Onanga Ndiaye—a diplomat of Senegalese origin—would remain foreign minister in the first cabinet of the Fifth Republic. Two days earlier, President Bassirou Diomaye Faye attended the inauguration of President Brice Oligui Nguema alongside a cohort of regional leaders.

taipeitimes.com

Africa Intelligence reported that Donald Trump’s special adviser on Africa, Massad Boulos, used the occasion to explore triangular co-operation among Dakar, Washington and Libreville.

Libreville’s choice of a Senegalese-born foreign minister operates on three registers: it appropriates Senegal’s democratic legitimacy, reassures investors unsettled by the 2023 coup, and opens a personal conduit to Dakar’s mediation networks. Early signs suggest that Gabon will establish an inter-faith advisory council modelled on Senegal’s National Committee for Dialogue, thereby institutionalising pluralism in a country only recently emerging from authoritarian stagnation.

Europe’s Symbolic Economy

France, recalibrating its posture after the draw-down of Operation Barkhane, now seeks partnership rather than tutelage. Africa Intelligence confirmed on 9 May that a Franco-Senegalese seminar is being prepared for later this year, with invitations dispatched to Prime Minister François Bayrou and senior cabinet colleagues. Paris intends to foreground religious diplomacy—and by implication Senegal’s moral capital—as an antidote to anti-neo-colonial discourse.

European diplomats, however, have been cautioned by Senegalese civil-society coalitions not to instrumentalise religious language as mere veneer. Memories of the Central African Republic, where Christian-coded rhetoric aggravated Muslim grievances, remain vivid. Any European engagement must therefore respect what local theologians call the “economy of symbol”—an ecology in which religious language carries deep affective weight.

Continental Reverberations

Dakar’s influence now extends beyond West Africa. On 8 May Ethiopia’s Inter-Religious Council announced a pan-African conference on faith communities and the Sustainable Development Goals to be held in Addis Ababa on 13–14 May, explicitly citing April’s Dakar colloquium as inspiration. The African Union’s Peace and Security Council is expected to integrate the Addis and Dakar recommendations into its 2026-2030 action plan, and a draft AU charter on religious diplomacy—still under negotiation—would establish a High-Level Panel on Faith and Mediation, with Senegal the presumptive inaugural chair.

Implications for Multilateral Policy

For diplomatic missions operating in West Africa three lessons stand out. First, religious literacy is now integral to risk assessment and opportunity mapping. Ignoring the moral register leaves critical intelligence untapped. Second, aid conditionality must account for reputational externalities: sweeping funding freezes can erode the very pluralist ecosystems that make partners resilient. Third, pluralism is not self-executing; it requires modest but sustained fiscal investment in mediating institutions, educational content and inter-faith early-warning systems.

Senegal’s 2025 trajectory demonstrates that religious diplomacy is no longer a rhetorical accessory but a functional instrument of statecraft. By converting moral authority into strategic leverage, Dakar has preserved security guarantees amid financial retrenchment, attracted diversified investment, and exported stabilising norms to Gabon and the wider continent. For practitioners, the imperative is clear: engage with the faith-based dimensions of African diplomacy now—or risk strategic myopia as the continent forges an indigenous synthesis of theology and geopolitics.

A Forward-Looking Agenda

Three research fronts deserve immediate attention. First, rigorous measurement of the “peace dividend” generated by religious diplomacy could inform donor allocation and quell scepticism in budget ministries. Second, comparative work across francophone and anglophone contexts would illuminate the conditions under which pluralism translates most effectively into diplomatic capital. Third, a gender lens is overdue: women’s religious networks, though often informal, have a demonstrable record in day-to-day dispute resolution and deserve systematic inclusion in both scholarship and policy design.