Ce qu’il faut retenir

At Tangier’s Hotel Andalucia, Senegal’s supporter federation, the “12e Gaïndé,” sustains a palpable matchday energy while already planning the next global rendezvous.

- Ce qu’il faut retenir

- Tangier’s Hotel Andalucia: Football, drums, and logistics

- US visa restrictions: a new variable for 2026 travel

- Why Senegal’s supporters read the policy as a test of trust

- Sports diplomacy in practice: federation, state, FIFA

- The “ambassador” argument and the return pledge

- Voices from the stands: pride, not exile

- Calendar and uncertainty: what remains unanswered

- Contexte

- Acteurs

- Scénarios

US visa restrictions announced in mid-December, including a new deposit requirement for applicants from listed countries, introduce uncertainty for travel to the 2026 World Cup in North America.

Supporter leaders frame their role as informal diplomats, highlighting written return pledges and a track record of coming back after trips, while expressing confidence in the Senegal–US relationship.

Tangier’s Hotel Andalucia: Football, drums, and logistics

A simple push through the Hotel Andalucia doors, on Tangier’s heights, captures the scene: piano notes, drums, and rolling chants compete in a single, crowded soundscape. The Lions’ pursuit of a second star has reignited a national fire, and the “12e Gaïndé” is determined to carry it into the semi-final hurdle against Egypt.

On a balcony above the bustle, Issa Laye Diop, the federation’s president, receives visitors in national colors, his supporter’s insignia firmly set. Even with AFCON dominating every conversation, he signals a parallel agenda: planning, mobilization, and animation for the World Cup arriving in five months, he explains (source text).

US visa restrictions: a new variable for 2026 travel

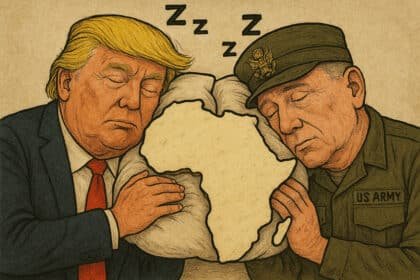

Behind the chants, the message from Washington has become the discreet topic that travels from room to room. Since the December 16 announcement adding Senegal to a list of countries facing temporary visa restrictions under the Trump administration, a practical question now shadows the dream: can supporters follow their team to the United States, Canada, and Mexico for the next World Cup?

The concern is sharpened by the requirement, effective from January 8 in the source text, that applicants from the countries concerned must lodge a deposit ranging from 5,000 to 15,000 US dollars when filing a visa request. The measure is described as entering into force on January 21 and presented as intended to “protect the security of the United States,” according to the White House (source text).

Why Senegal’s supporters read the policy as a test of trust

For a movement that files between 800 and 1,000 visa requests during World Cups, the announcement lands less as a bureaucratic inconvenience than as a signal about perceived intent. Officially, the policy is linked to an overstay rate judged too high, and it follows a broader wave of bans that had already touched twelve other countries and now affects twenty additional African states, including Senegal (source text).

Within the Senegalese supporter camp, the dominant tone is incomprehension rather than confrontation. Yet it is not despair. Issa Laye Diop insists the group remains confident, arguing that Senegal–US relations are “of quality” and that visas have historically been issued in a clear and transparent manner on both sides (source text).

Sports diplomacy in practice: federation, state, FIFA

In the supporters’ account, the coming World Cup is not only a sporting itinerary but a diplomatic space with multiple gatekeepers. Issa Laye Diop describes “a whole aspect of sports diplomacy” taking shape and says the group counts on the Head of State, President Diomaye Faye, as well as federal authorities, while also underlining the role of FIFA as organizer (source text).

The reasoning is pragmatic: if restrictions threaten participation, he expects national authorities and football institutions to engage, because a federation also needs its supporters—an element of atmosphere, visibility, and narrative that modern football increasingly treats as part of the product (source text).

The “ambassador” argument and the return pledge

In the hotel gardens, rehearsal takes a disciplined form: songs are repeated until they synchronize, while women prepare the midday meal in the kitchens. The display of national attachment is not left to improvisation; it is curated as representation. That is where the association’s internal governance becomes central to its legitimacy in a visa-sensitive environment.

Mbar Dione, the group’s secretary-general, presents the rule as both ethical and strategic. He says the priority is to be “ambassadors of Senegal” and that every member traveling signs a written commitment stating they will return. He adds that, on each trip, no member has remained abroad; everyone has always returned home. “No one will stay in the United States,” he says (source text).

Voices from the stands: pride, not exile

Among the women supporters, the same position is voiced with a calm that reads as resolve rather than defensiveness. Fatimata Yal says living in the United States, Qatar, Argentina, or elsewhere is not her dream. Her objective is to represent Senegal, support the “12e Gaïndé” and the Lions, and, if a visa is refused on suspicion she might stay, she would not “make a fuss,” choosing to watch games in Canada or Mexico instead (source text).

Issa Laye Diop adds a social reality often missing from migration-focused assumptions: many supporters have businesses, families, and jobs in Senegal. Some work in state services; others are entrepreneurs or business leaders, he says. In this framing, travel is a temporary mission of visibility, not a one-way departure (source text).

Calendar and uncertainty: what remains unanswered

The story, as told on the ground, mixes concrete dates with open questions. The deposit requirement is described as applying from January 8 for nationals of listed countries, with the broader measure entering into force on January 21 (source text). Meanwhile, supporters also cite anticipated fixtures, including Senegal–France and Senegal–Norway in New York, as focal points for planning (source text).

Institutional silence adds to the uncertainty. The Senegalese Football Federation, contacted repeatedly in the source text, did not respond to requests. For the supporter movement, that absence keeps attention fixed on informal assurances and on the hope that sporting stakes will encourage a workable path for legitimate travel.

Contexte

The “12e Gaïndé” is presented as a structured supporter federation that travels with Senegal’s national team and organizes chants, mobilization, and matchday animation (source text). Its leadership portrays the group as a cultural asset as much as a crowd.

The visa measure described in the source text is linked to US domestic security framing and to concerns about visa overstays. The policy’s extension to multiple African countries transforms what might have been a Senegal-only issue into a wider signal watched across the continent.

Acteurs

Issa Laye Diop appears in the source text as president of the “12e Gaïndé,” speaking on planning, confidence in bilateral relations, and the role of sports diplomacy.

Mbar Dione, cited as secretary-general, explains internal travel commitments and the group’s “ambassador” posture. Fatimata Yal offers a supporter’s personal perspective. The White House is cited for the policy’s stated objective, and FIFA is referenced as organizer of the World Cup (source text).

Scénarios

If visa procedures tighten in practice, the supporters suggest adaptive routes, including attending matches in Canada or Mexico, while maintaining their identity as a traveling cultural delegation (source text).

If authorities and football institutions engage, as supporters anticipate, the group’s disciplined return commitments and documented organization could support a narrative of facilitated, time-limited travel consistent with the policy’s stated aims (source text).