Ce qu’il faut retenir

French president Emmanuel Macron’s attempts to navigate the explosive memory of colonial rule have collided with Algeria’s own politics of identity. From his 2017 campaign denunciation of colonisation as a “crime against humanity” to his present refusal to apologise, each pivot has widened the diplomatic fault line.

Algiers has now placed on the parliamentary agenda a bill criminalising French colonialism, a move that institutionalises anger and complicates co-operation on energy, security and migration. Paris, viewing the initiative as hostile, risks seeing yet another North African door swing toward rival partners such as Moscow and Ankara.

Historical Context of Memory Politics

Macron first touched the raw nerve during a February 2017 visit to Algiers, when, still a candidate, he described French rule as barbaric and called for contrition. The remark electrified Algerian public opinion, but stirred backlash among French veterans’ groups and segments of the right, foreshadowing a domestic constraint.

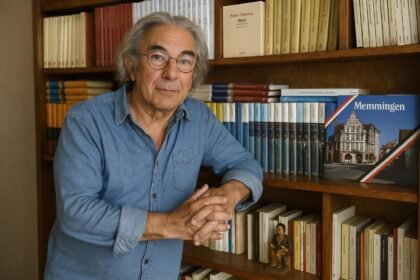

Eager to prove that gestures could replace apologies, the Élysée commissioned historian Benjamin Stora in 2021 to map confidence-building steps. His report advocated symbolic recognitions, shared archives and joint youth programs. Only a handful of recommendations, such as partial archive openings, have been implemented, feeding Algerian doubts about Paris’s resolve.

Tensions intensified further in March 2023 when Macron, seeking to reset ties with Rabat, endorsed Morocco’s autonomy plan for Western Sahara. Algerian officials interpreted the gesture as a diplomatic affront that undermined their support for the Polisario. Within days, Algerian press resurrected calls for a law branding French colonialism a war crime.

Diplomatic Calendar

The legislative proposal brandished in Algiers falls within a wider electoral season that will culminate in the 2024 presidential race. Algerian lawmakers see leverage in foregrounding colonial grievances as unemployment and inflation bite at home. For Paris, the timing overlaps with European elections, where anti-immigration rhetoric already dominates.

Another date on the horizon is November 2024, the sixtieth anniversary of the Algerian constitution. Ceremonies will likely amplify nationalist discourse, complicating any discreet French initiative. Diplomats on both shores privately concede that meaningful movement may be deferred until after these commemorations recede from the spotlight.

Key Actors at Play

Inside the Algerian system, the lower house sponsors the criminalisation bill, but ultimate arbitration rests with the presidency and the powerful High Security Council. Observers note that President Abdelmadjid Tebboune can either let the text proceed, signalling firmness, or quietly delay it, using parliamentary procedure to keep options open.

On the French side, the issue mixes Élysée diplomacy with parliamentary dynamics where opposition parties court the Pied-noir constituency. Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna must therefore calibrate public statements to maintain room for technical cooperation on visas and border management, while shielding Macron from charges of capitulation.

Third-party players are capitalising. Spain welcomes Paris’s recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara as indirect support for its own position. Rabat points to the same declaration to pressure Algiers on the Polisario Front. Russia, already entrenched in the Sahel, courts Algerian defence procurement by framing itself as a steadfast historical ally.

French energy major TotalEnergies, which signed a $1.5 billion gas framework with Sonatrach in 2022, has kept a low profile. Executives privily signal that contractual stability rests on insulating economic dialogue from history debates. Algerian trade unions, however, argue that any future deals must carry social clauses acknowledging past exploitation.

Possible Scenarios Ahead

If the Algerian bill passes in its current form, French companies bidding for hydrocarbons or renewable projects could face public scrutiny, but outright expropriation is considered unlikely. More probable is a tightening of cultural visas and a temporary freeze of security dialogues, measures that satisfy domestic opinion without derailing energy contracts.

A second scenario, favoured by some European diplomats, envisages a calibrated Algerian climb-down once electoral cycles conclude. Paris would reciprocate through additional archive releases and perhaps a joint commission on cemetery rehabilitation. Such incrementalism lacks the drama of an apology, yet experience suggests that quiet, accumulative gestures often outlast public rhetoric.

Regardless of the trajectory, the episode illustrates how memory politics shapes Europe’s broader partnership with North Africa at a moment of fierce geo-strategic competition. For African observers from Dakar to Kinshasa, the France-Algeria friction serves as a reminder that colonial legacies remain active variables in contemporary diplomacy.