Eritrea’s unexpected withdrawal

Eritrea stunned its neighbours on 12 December by announcing an immediate withdrawal from the Inter-governmental Authority on Development, the eight-member bloc headquartered in Djibouti. In its communiqué, Asmara argued that IGAD “failed and continues to fail its statutory obligations”, providing “no tangible strategic benefit” nor meaningful contribution to regional stability (Asmara communiqué, 12 December).

The legal and political grievances

Asmara’s statement revives a pattern first seen in 2007, when Eritrea suspended its membership for similar reasons before returning in 2023. Officials now claim the bloc has compromised “its own legitimacy and legal mandate” and, by extension, offers Eritreans little incentive to remain engaged in the council meetings, technical committees or conflict-resolution forums it routinely convenes.

Sudan war: diverging bets within IGAD

Behind the legal language lies a sharper geopolitical calculation. According to CNRS research director Marc Lavergne, all other IGAD members back Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces against the national army, whose chief external supporter is Egypt. By distancing itself, Eritrea aligns indirectly with Cairo’s outlook on Khartoum’s battlefield dynamics, widening an already visible rift inside the bloc.

The Sudan war has split the Horn into rival diplomatic camps and exposed the bloc’s limited leverage. IGAD-led cease-fire initiatives have stalled for months, giving credence to Asmara’s accusation that the organisation is unable to translate communiqués into enforceable action. Observers note that Eritrea attended none of IGAD’s Sudan sessions after its formal return last year.

Yet the timing of Asmara’s move is striking. IGAD ministers had planned a new mediation round in Nairobi before the end of the year. Eritrea’s exit removes a dissenting voice that could have complicated consensus but also deprives talks of a neighbour with intimate knowledge of Sudanese factions and border logistics.

The Nile dam and Cairo’s shadow strategy

Beyond Sudan, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam looms large. Egypt fears the hydropower project will curtail Nile flows and has sought partners to pressure Addis Ababa. Lavergne argues that Eritrea’s withdrawal forms part of Cairo’s broader effort to “encircle and dismember” its upstream rival, an allegation Addis officials dismiss as propaganda.

Eritrea, which fought alongside Ethiopia until their 1998-2000 war, has quietly deepened security ties with Egypt over the past decade. Its departure from a bloc led by former Ethiopian foreign minister Workneh Gebeyehu therefore signals a diplomatic gesture toward Cairo as much as a rebuke to Addis Ababa’s growing clout in regional institutions.

Addis–Asmara rivalry rekindled

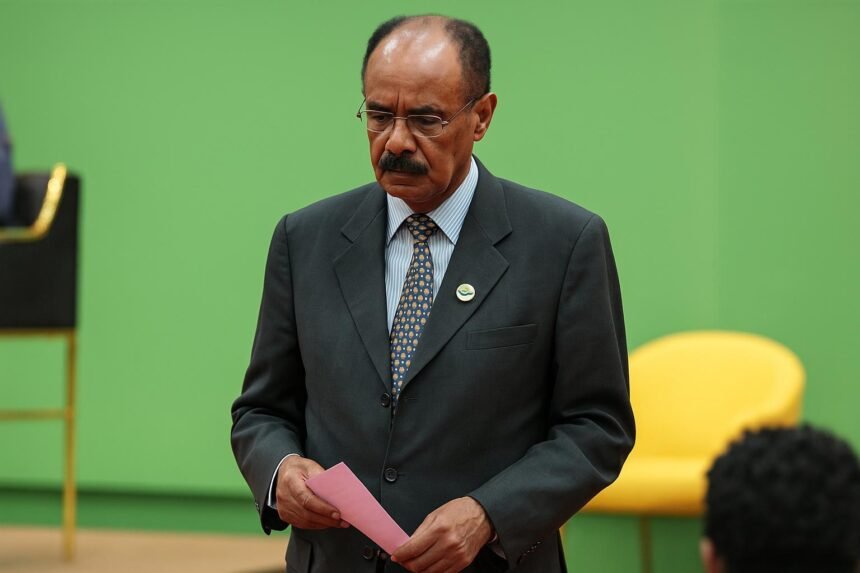

Relations between Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and President Isaias Afwerki warmed briefly during the 2018 peace accord but soured again amid border demarcation delays and divergent strategies in Tigray. Eritrea now portrays IGAD as an Ethiopian platform, pointing to the location of its secretariat in Djibouti and to what it calls Addis Ababa’s “disproportionate influence”.

Addis Ababa downplays the critique, insisting that IGAD decisions require unanimity and that the body remains essential for coordinating climate, trade and migration policies across the Horn. Diplomatic sources in Nairobi nevertheless concede that Workneh’s Ethiopian background complicates perceptions of neutrality at a moment of renewed tension along the Eritrea–Ethiopia border.

Eritrea’s decision also reflects its tradition of strategic solitude. Since independence in 1993, the country has skipped elections and maintained limited cooperation forums, preferring bilateral security pacts and hard-border controls. Observers therefore doubt Asmara will seek an alternative multilateral platform; withdrawal is designed less to join a new club than to keep rivals off balance.

Can IGAD reinvent itself?

In Djibouti, the secretariat “regrets” the move and has urged Eritrea to reconsider, noting that the country has not taken part in any IGAD activity since re-admission in 2023. Officials say budgets, programmes and staffing remain unchanged and that the bloc has learned to operate without Asmara, having functioned for sixteen years during its earlier absence.

Still, the withdrawal underscores a credibility problem already flagged by donors and African Union envoys: too many communiqués, too few implementable decisions. Analysts suggest that IGAD’s mediation toolbox—once praised for resolving Kenya’s 2007 crisis—needs heavier financial firepower and a clearer division of labour with the AU’s Peace and Security Council to regain momentum.

Continental integration at a crossroads

Eritrea’s exit is more than a Horn-of-Africa story; it serves as a cautionary tale for continental integration efforts, from ECOWAS to CEMAC. The incident shows how regional blocs can be weakened by member states perceiving inequitable influence. Whether IGAD adapts or fragments will inform debates over the African Continental Free Trade Area’s own governance model.