Ce qu’il faut retenir

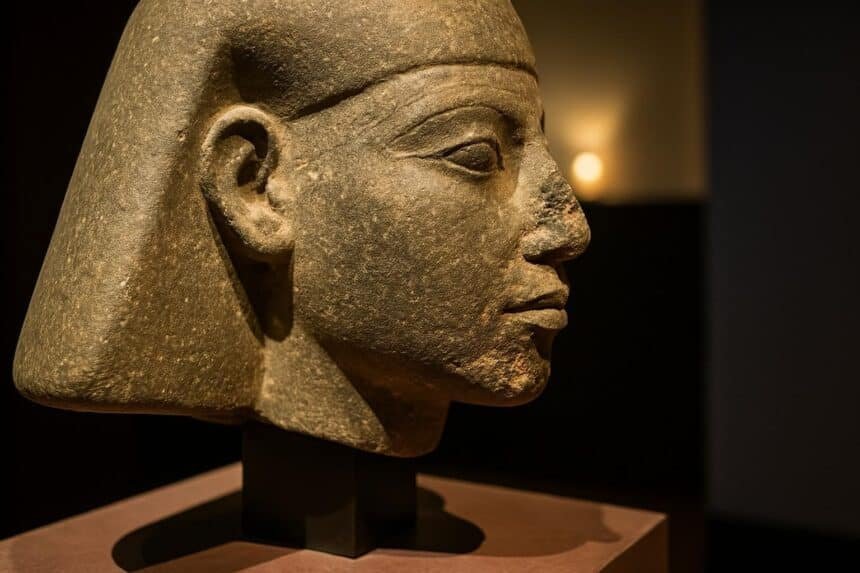

The Netherlands has committed to return a 3,500-year-old limestone head of a high official from the reign of Thutmose III to Cairo after confirming it was smuggled during the turbulence of the 2011-2012 Arab Spring; the decision coincided with the inaugural events of Egypt’s long-awaited Grand Egyptian Museum.

A Timely Gesture for Egypt’s Mega-Museum

The Dutch pledge was made personally by outgoing Prime Minister Dick Schoof at the Giza opening ceremony, an occasion designed to showcase a US$1.2 billion complex that houses 100,000 artefacts, including the complete Tutankhamun collection. By aligning with the fanfare, The Hague signalled that repatriation can be part of proactive cultural diplomacy rather than a reluctant legal remedy.

Egyptian officials, who have long argued that heritage restitution is a prerequisite for equitable global cultural exchanges, welcomed the announcement as “deeply meaningful to Egypt’s identity”. Their language mirrors a broader African narrative: priceless objects taken during war, colonial rule or periods of instability are not mere curios, but anchors of collective memory and resources for development.

Tracing an Illicit Journey from Nile to Maas

According to the Dutch Information & Heritage Inspectorate, the limestone head probably left Egypt amid the chaos that toppled President Hosni Mubarak. Its arrival, a decade later, at the prestigious European Fine Art Foundation fair in Maastricht illustrates the long, opaque itineraries that mediate between tomb looters in Upper Egypt and collectors in Western capitals.

The chain unravelled after an anonymous tip prompted Dutch police to verify provenance records. The dealer, facing incontrovertible documentation gaps, voluntarily surrendered the piece. Experts note that such collaborative outcomes are still rare; many cases languish because national authorities lack either the legal tools or political will to interrogate lucrative art markets.

Restitution as Emerging Norm in Europe

Over the past five years, France, Germany and Belgium have enacted or proposed laws facilitating the return of artefacts acquired under questionable circumstances. The Netherlands adopted similar guidelines in 2020, emphasising “shared heritage”. While critics see reactive image-management, proponents argue that institutionalising restitution prevents diplomatic friction and nurtures a twenty-first-century ethic of partnership.

Cairo has mastered this diplomatic lever. Since 2016 it has recovered more than 29,000 items through negotiation, litigation or seizure in transit hubs such as New York. Each victory reinforces its bargaining power on marquee pieces like the Rosetta Stone, currently showcased in London, demonstrating how incremental gains can recalibrate global museum geopolitics.

Implications for African Cultural Sovereignty

Across the continent, curators argue that heritage is a strategic asset capable of attracting tourism, inspiring creative industries and undergirding historical scholarship. Nigeria’s planned Edo Museum of West African Art, Senegal’s Museum of Black Civilisations and Ethiopia’s restitution task force are part of a policy ecosystem that treats cultural patrimony as intertwined with economic diversification and nation branding.

Yet funding gaps, fragile storage conditions and uneven museological training create genuine concerns about capacity. European interlocutors sometimes invoke these factors when negotiating transfer timelines. Egypt’s experience with the Grand Egyptian Museum, built through Japanese loans and extensive conservation partnerships, indicates that African states can leverage multilateral finance to match the technical standards demanded by UNESCO conventions.

What Next for Continental Claims?

In the wake of the Dutch decision, legal analysts forecast renewed momentum for claimants preparing dossiers on objects circulating in private fairs from Paris to Los Angeles. Digital provenance databases, satellite imagery of looting sites and expanded INTERPOL alerts are enhancing the evidentiary base, reducing the plausible deniability that once protected illicit traders.

African negotiators also watch closely the soft-power dividends reaped by restituting governments. France’s loan of returned Benin bronzes for the “Art du Bénin” exhibition in Cotonou drew praise across West Africa, while Germany’s agreement on the Benin Dialogue Group boosted its image in Abuja. The Netherlands now hopes for comparable goodwill as it deepens ties with African partners.

For Egypt, the imminent hand-over of the Thutmose III head is symbolic rather than sensational, yet it reinforces a cumulative strategy that many in Africa’s diplomatic community observe with interest. Restitution, once considered a moral debate, is consolidating into a material variable of foreign policy—one that blends law, economics and identity without firing a single shot.