Ce qu’il faut retenir

The measured yet forceful interventions of Niger and Burkina Faso at the 78th UN General Assembly have exposed widening tonal differences inside African diplomacy. Congo-Brazzaville, seeking to preserve constructive ties with Paris while defending continental agency, must now calibrate its multilateral toolbox with heightened finesse.

Sahel Rebuke at UN General Assembly

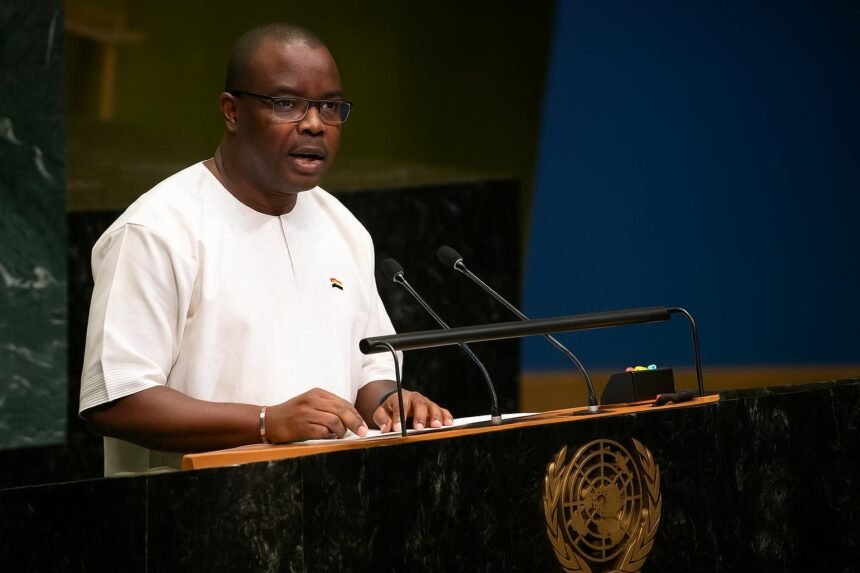

On 27 September, Interim Prime Minister Lamine Zeine Ali Mahaman used the marble podium to recount colonial atrocities, urging France to accept responsibility for “unsold debts of memory”. His address echoed the fiery speech of Burkina Faso’s Jean-Emmanuel Ouédraogo, who labelled the United Nations Security Council a “grand troublemaker” after eighty years of operation.

Both leaders portrayed the international system as structurally indifferent to Sahelian suffering, citing a disputed UN report on child casualties in Burkina Faso and the dismantling of French security partnerships in Niamey. The assertive rhetoric resonated inside the General Assembly hall yet also underscored the political distance between transitional regimes and traditional multilateral interlocutors.

Brazzaville’s Multilateral Calculus

Congo-Brazzaville followed the debate with particular care. President Denis Sassou Nguesso has long framed his external doctrine around moderation, mediation and forestry diplomacy. Brazzaville’s envoys emphasise constructive engagement with the Security Council, not confrontation, while still advocating reform of veto prerogatives and greater African representation in line with the Ezulwini Consensus.

Diplomats in New York note that Congo’s permanent mission is quietly canvassing support for a CEMAC-centric caucus able to bridge the gap between the Sahel’s insurgent posture and the gradualist preferences of coastal states. The objective is to protect regional cohesion ahead of critical votes on peacekeeping budgets and climate-finance packages.

Soft Power and Historical Memory

History weighs differently on Brazzaville. The city hosted de Gaulle’s 1944 conference that opened France’s imperial reform, a legacy the Congolese authorities recast today as proof of their capacity to convene dialogue. Cultural institutes, music festivals and the Pan-African Music Festival are deployed to project a reconciliatory brand rather than pursue retroactive accountability.

Yet officials privately concede that Niger’s demand for an international commission on colonial crimes taps into a broader continental conversation about restitution, archives and dignified remembrance. Brazzaville’s Ministry of Cultural Industries is therefore exploring joint exhibits with Sahelian museums, an initiative that could channel emotive narratives into cooperative soft-power programming.

Regional Security Scenarios

Militarily, the divergence is starker. Burkina Faso and Niger have embraced the Alliance of Sahel States, pledging mutual defence outside French tutelage. Congo-Brazzaville remains invested in multilateral mechanisms such as the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region and the AU’s Standby Force, platforms perceived as more predictable for managing transnational threats.

Security analysts caution that a prolonged diplomatic standoff between Paris and Niamey may jeopardise logistics corridors serving CEMAC importers through Nigerien territory. Brazzaville’s Port Autonome relies on seamless hinterland access to maintain competitiveness. Maintaining open channels with both Sahelian juntas and European partners is therefore framed as an economic imperative, not merely a political nicety.

Towards a Nuanced African Voice

What emerges is an increasingly plural continental repertoire: strident denunciation in the Sahel, calibrated persuasion along the Congo River. AU chair Moussa Faki Mahamat has hinted at convening informal retreats to craft common messaging before the 2024 Summit of the Future, where UN reform will dominate the agenda.

For Brazzaville, the coming months offer a chance to reinforce its profile as an honest broker. By hosting preparatory seminars that include Sahelian representatives, Congolese diplomacy can demonstrate that assertiveness and engagement are not mutually exclusive, and that Africa’s collective influence rises when its internal conversations accommodate both indignation and institution-building.